«Have you had breakfast?» I asked.

She hesitated. «I’m fine.»

That meant no. «There’s a coffee shop next door. Go get yourself something.»

«Tell Marco I sent you. He’ll put it on my tab.»

«I don’t need…»

«You can’t work on an empty stomach. Go. I’ll be here when you get back.»

She went. I used the time to clear off the desk in the back office. Moved boxes of inventory.

The couch was old, the cushions sagging, but it was clean. I found a blanket in the storage closet. A pillow that smelled like mothballs but would do.

Jennifer came back 15 minutes later with a coffee and a muffin wrapped in paper.

«Thank you,» she said. «I’ll pay you back when I get paid.»

«Don’t worry about it.»

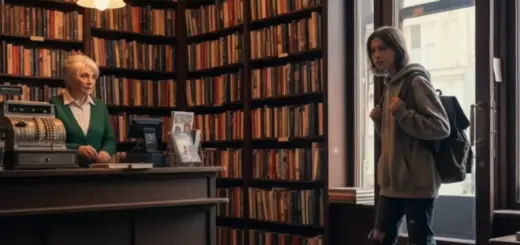

I spent the morning training her. How to work the register. How the shelves were organized.

Fiction alphabetical by author. Non-fiction by subject. The poetry section in the back corner where the light was best.

She learned fast. Asked good questions. Wrote things down in a small notebook she pulled from her backpack.

«Do you get a lot of customers?» she asked.

«Not like we used to. People buy books online now.»

«That’s sad.»

«It is what it is.»

She ran her hand along a shelf of hardcovers. «These are beautiful though. You can’t get this from a screen.»

I liked her already.

By lunch, I let her handle the register while I did inventory in the back. I watched through the doorway. She was careful with the customers, polite.

She recommended books to a woman looking for something for her daughter. During a slow stretch in the afternoon, I found her sitting on the floor in the poetry section.

Her notebook open. She was writing something, then crossing it out. «What are you working on?» I asked.

She looked up startled. «Nothing. Just.» She closed the notebook. «Stories, I guess.»

«You write.»

«Sort of. It’s stupid.»

«It’s not stupid.»

She shrugged. «Books were kind of my friends when I was younger. When things got bad at home.»

I sat down on the stepstool near her. «What happened at home, Jennifer?»

She was quiet for a long time. Picked at the edge of her notebook.

«My mom had problems,» she finally said. «Drugs mostly. It started after I was born. I don’t really remember a time before it.»

«I’m sorry.»

«I took care of her. When I was old enough. 10 maybe. I’d find her passed out on the couch, or in the bathroom.»

«I got good at hiding things from the neighbors. Making excuses.» She said it flat. Like she was reading from a list.

«That’s a lot for a kid to handle.»

«I didn’t have a choice.» She looked up at me. «I found her when she died. I was 12. Came home from school and she was in the bathroom.»

«I called 911. But she was already gone.»

My chest tightened. «Jennifer.»

«It’s okay. It was 4 years ago.» She closed her notebook. «After that, it was foster care. Then the orphanage. That place was awful.»

«Cold. They didn’t care about us. We were just numbers.»

«So you left.»

«Yeah. Last year. I turned 15, and I just walked out. Been on my own since.»

She said it like it was simple. Like being homeless at 15 was just another thing that happened.

I understood loss. I understood loneliness. It hit me then.

Sitting on that stepstool in the poetry section. Jennifer’s story settling into my bones. I’d been alone too.

2 years ago, my world fell apart. Paul died on a Thursday morning. Heart attack.

Sudden, no warning. I woke up and he was already gone in the bed next to me. Just gone.

We’d been married 40 years. Built this bookstore together from nothing. It was ours.

Every shelf. Every book. Every creak in the floorboards.

The funeral was small. Paul didn’t have much family left. Chris came.

My son. But he stayed in the back. Spent half the service on his phone. Left right after without saying much.

I spent 3 months in a fog. Running the store because I didn’t know what else to do. The apartment upstairs felt too big without Paul.

The silence pressed down on everything. Then Chris showed up one afternoon. He had a business plan.

Subscription boxes. Curated products for young professionals. He needed $350,000 to get started.

He wanted me to sell William’s bookstore. «Think about it, Mom,» he said. «This place barely breaks even. You’re working yourself to death for what?»

«Dad’s gone. You don’t need to keep doing this.»

I stared at him. «This store is all I have left of your father.»

«It’s a building. It’s inventory. Dad wouldn’t want you struggling.»

«I’m not selling.»

His face changed. Got hard. «You’re choosing this over helping your own son?»

«I’m not choosing anything. I’m keeping what your father and I built.»

«Dusty books over your son’s future. Got it.»

«Chris.»

«Forget it.» He stood up. Grabbed his coat.

«Don’t expect me to be around to watch you struggle. I’m done.»

He left. Didn’t call. Didn’t visit. Two years of silence.

I lost Paul. Then I lost Chris by his own choice. I ended up completely alone.

Just like Jennifer. We’d both lost the people we loved. Both ended up with nobody.

I looked at her sitting there on the floor. This kid who’d survived things she shouldn’t have had to survive.

And I saw the timeline clear as day. Chris and Amanda dated 17 years ago, maybe 16. Jennifer was 16 now. Born after Amanda left.

It could be nothing. Or it could be everything. I needed proof.

Real proof. Before I did anything that couldn’t be undone.

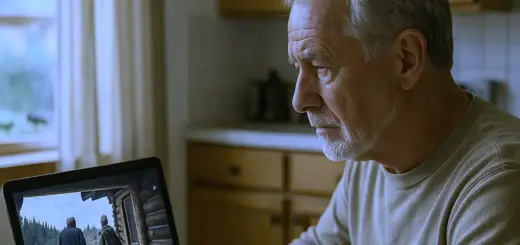

That night, after Jennifer went to sleep on the couch in the back office, I sat at the computer upstairs. Searched for DNA tests.

Found a company that did ancestry matching. Ordered two kits. They arrived three days later.

Jennifer was restocking the young adult section when I brought them downstairs.

«Hey,» I said. «I got something kind of random.»

She turned around. «What’s that?»

I held up the boxes. «Ancestry DNA kits. I read this book about genetics a few weeks ago. Got me curious about my family tree.»

«I ordered two by accident. Wanna try it with me?»

She looked at the box. «Really?»

«Could be fun. See where our families came from.»

«I don’t know much about my family. Just my mom.»

«That’s okay. It might show you something interesting.»

She shrugged. «Sure. Why not?»

We opened the kits at the counter. Read the instructions together. The process was simple.

Swab your cheek. Seal the tube. Mail it back.

Jennifer did hers first. I watched her spit into the tube. Cap it. Shake it.

«That’s it?» she asked.

«That’s it.» I did mine.

We packaged them up, walked to the post office together, and dropped them in the mail slot.

«How long does it take?» Jennifer asked.

«Three weeks, maybe four.»

«That’s a long time.»

«Good things take time.»

She smiled. First real smile I’d seen from her. We walked back to the bookstore in the November cold.

The sun was setting early. The streetlights were already on. Three weeks until I’d know for sure.

Three weeks until I’d have proof. And then I’d figure out what to do about Chris.

The waiting started the next morning. Jennifer showed up at 8:30 with two coffees from Marco’s. Set one on the counter in front of me.

«Thought I’d return the favor,» she said.

It became our routine. Morning coffee, her behind the register while I unpacked new inventory, lunch shared in the back office.

Her asking questions about books I’d loved. Me learning bits and pieces about who she was.

The first week passed slow. Each day I watched her, looking for more signs, more proof beyond a familiar face. And a timeline that fit.

She worked hard, never complained, never showed up late. On Thursday, I found her reading in the poetry section during her break. The same spot she’d been that first day.

«Find something good?» I asked.

She held up the book. «Mary Oliver. My mom used to read poetry,» she said, «when I was little, before things got bad.»

I sat down on the stepstool. «What was she like? Before?»

Jennifer’s face softened. «She was good, really good. She’d make up voices for different characters when she read to me. She loved books almost as much as I do.»

«Almost?»

A small smile. «I might love them more.»

«What happened to her? I mean, what changed?»

Jennifer closed the book. Ran her finger along the spine. «I think she was sad. My whole life, probably.»

«Her parents kicked her out when she got pregnant. She was 20. She tried to make it work, but I don’t think she ever stopped being heartbroken about it.»

20, same age Amanda was when Chris dated her. «The drugs started when you were young?»

«Yeah. I remember being maybe 5 or 6, finding needles in the bathroom. Not knowing what they were.»

She paused. «By the time I was 10, I was the one taking care of her.»

«That’s too much for a kid.»

«I didn’t have a choice.» She opened the book again. Stared at the pages without reading.

«But there were good days. Days when she’d be clean for a week, sometimes two. She’d take me to the library. We’d check out stacks of books.»

«She’d read poetry to me at night.»

«What kind?»

«All kinds. Neruda? Dickinson? Frost? She had this old collection. Torn cover, pages falling out.»

«She gave it to me right before…» Jennifer stopped. «Right before things got really bad. Told me to keep it safe.»

«Do you still have it?»

She nodded. Reached into her backpack and pulled out a small book. The cover was held together with tape. Pages yellowed and bent.

«I carried it with me everywhere. On the streets, in the shelters. It’s the only thing I have from her.»

She handed it to me. I opened it carefully. Inside the front cover, written in faded ink.

«For my Jennifer. Love finds a way. Mom.»

My throat tightened. «This is beautiful.»

«She wrote that when I was 11, a few months before she died.» Jennifer took the book back. Held it close.

«Sometimes I read it and try to remember her voice. The way she’d emphasize certain words. Make them sound like music.»

«Is that why you write? To remember her?»

«Kind of.» She put the book away. «I write the version of her I wish I’d had. The mom who stayed clean. Who took care of me instead of the other way around.»

«It’s stupid.»

«It’s not stupid. It’s survival.»

She looked at me. «That’s exactly what it is.»

The second week, Jennifer suggested we reorganize the young adult section. «It’s popular right now,» she said. «If we move it to the front window, more people might come in.»

She was right. We spent two days rearranging. She made little handwritten signs. Recommendations for different age groups.

Within three days, we’d sold more young adult books than we had all month.

«You’re good at this,» I told her.

She shrugged. «I just know what I would’ve wanted when I was younger. A place that felt like it was for me.»

On Wednesday of that week, an older couple came in looking for a book club recommendation. Jennifer suggested a few titles. Explained why each one would work.

They bought three books and asked if we hosted book clubs.

«Not currently,» I said.

After they left, Jennifer turned to me. «Could we? Host a book club?»

«You want to run it?»

«I could try. Once a month maybe. We could use the space in the back.»

«Let’s do it.»

Her whole face lit up. «Really?»

«Really.»

She threw herself into planning. Made flyers. Posted them around the neighborhood. By Friday, six people had signed up.

I watched her with customers that week. She had a way with people. Made them feel seen.

An older man came in looking for something to read to his grandson. Jennifer spent 20 minutes with him, pulling books. Explaining why each one mattered.

«You remind me of my daughter,» he said when he left. «She used to love books like this.»

Jennifer smiled, but after he left, she got quiet.

«You okay?» I asked.

«Yeah.» She restocked a shelf. «It’s just weird. People being nice.»

«You’re not used to it?»

«On the streets, you learn pretty fast who to trust. Most people look through you. Like you’re not there.»

She paused. «In the shelters, it’s worse. Everyone’s so angry, so tired. You keep your head down and stay out of the way.»

«What was the worst part?»

She thought about it. «The fear, I guess. Never knowing if someone was going to hurt you. Take your stuff.»

«I slept in doorways sometimes. Library bathrooms. Anywhere that felt safe for a few hours.»

«How did you survive?»

«I was careful. Stayed in public places during the day. Avoided certain streets at night.»