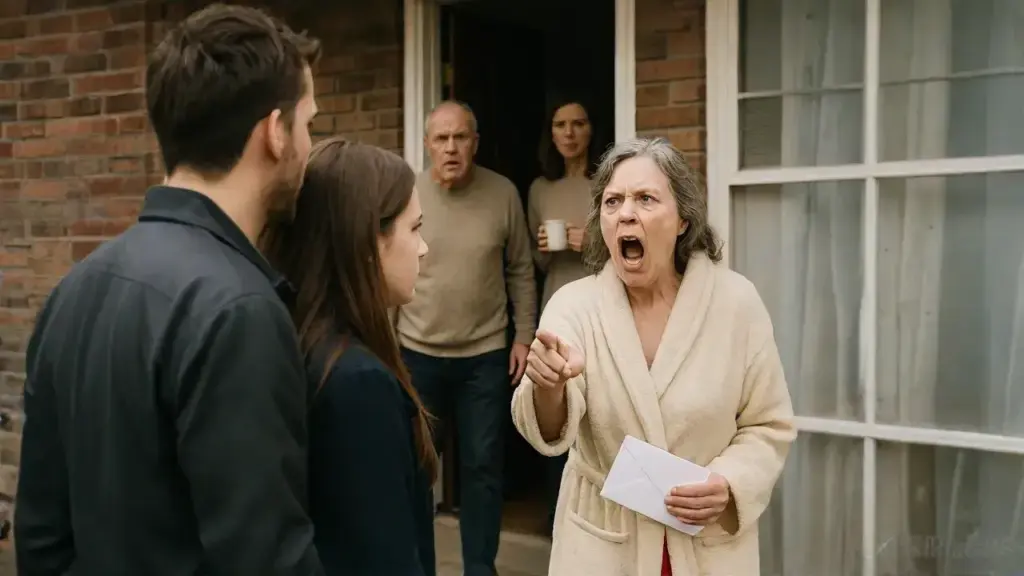

At Christmas, I was working a double shift in the ER. My parents and sister told my 16-year-old daughter there was no room for her at the table. She had to drive home alone and spend Christmas in an empty house. I didn’t make a scene. I took action instead. The next morning, my parents found a letter at their door and started screaming.

On Christmas Eve, I got home around 11:45 at night, dead on my feet. I’d done compressions on a man who insisted he was just tired. He was also blue.

That was that kind of shift. So when I saw Abby’s boots by the door, my first thought was, «Someone’s bleeding.» Then I saw her coat slumped on the armrest.

Her overnight bag was still zipped. And she was curled up on the couch in that tight, awkward sleep position, like she didn’t trust the furniture. I stood there, waiting for the logic to catch up.

She was supposed to be at my parents’. Overnight. Tradition. She begged to drive herself, just once. She was newly licensed and proud of it.

She even left early to be extra polite. My husband and I were both working late shifts, so the plan made sense. Until it didn’t.

«Abby?» I said softly.

She opened her eyes instantly, like she hadn’t really been sleeping. «Hey.»

«Why are you here?»

She sat up slowly and shrugged. «They said there wasn’t room.»

I blinked. «Room where?»

«At the table.» Her voice cracked halfway through. She tried to cover it with another shrug. It didn’t work.

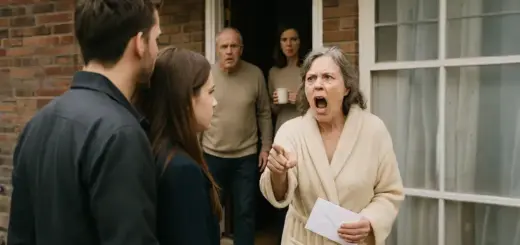

«They said they weren’t expecting me. That there were too many people already. Grandma said she couldn’t just pull up another chair last minute.»

«She looked stressed, like I was adding to her load.»

«You got there on time, though.»

«Yeah. Right on time. She opened the door and just… looked surprised. Like I’d shown up for the wrong holiday.»

She paused. «Then she said there wasn’t a bed left either. There it was. The backup excuse.»

«She said they didn’t want me driving back late, but also didn’t know where else to put me. So… I left.»

«Did anyone offer to drive you home?»

«Nope.»

I stared at her. «Did they at least let you eat?»

Another shrug. «The table was packed. Lily was in my usual seat. Grandpa was talking to her like she was royalty. No one looked at me.»

«Then Grandma said, ‘It’s just a full house this year.’ And Aunt Janelle nodded. So… I left.» She glanced at the table and added, «I made toast.»

I turned and saw it. A single slice on a paper towel, cold and slightly bent. Half a banana next to it. That was her Christmas dinner.

I felt something coil in my chest. Not anger. Not yet. Just that cold, glassy feeling right before the shatter.

«I wasn’t hungry anyway,» she said. «Not really.»

That’s when her eyes started to fill. She fought it. God, she tried. She looked up, blinked hard, and bit her lip like she could chew her way out of the emotion.

«They made it seem like I’d imposed,» she whispered. «Like showing up, after it was planned, was rude.»

And then she cried. Quiet. And slow. Like a faucet you can’t quite turn off.

«I was going to bring a pie,» she added. «But I thought they’d have enough food already.»

I sat next to her and put my arm around her shoulders. She leaned in without hesitation, like she’d been holding herself up out of spite.

After a while, she wiped her nose on her sleeve. «I know they don’t like you,» she said. «But I thought…» She cut herself off.

«You thought you were just the kid. Not part of it.»

She nodded. «They didn’t even say it meanly,» she added. «Just… like it was a practical problem. Like I was a folding chair they didn’t have space for.»

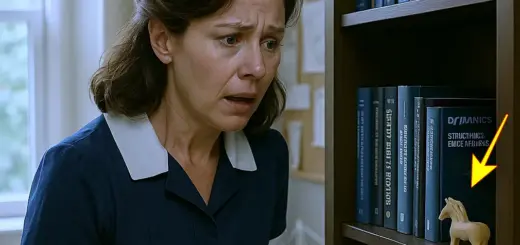

I didn’t go to bed right away. I sat in the kitchen, looking at her bag, still zipped. She’d packed it so carefully, picked out the sweater my mom said she liked, and brought a little tin of cookies she made herself.

I opened the fridge. There was nothing special in there. We hadn’t planned to back up Christmas. Why would we? We trusted them.

That’s the part I couldn’t get over. Not the cold cheese toast or the lack of food. Not even that she drove home alone in the dark.

It’s that they looked her in the eyes—this sweet, awkward, brave girl who showed up on time with cookies and a smile. And told her, with 28 people inside, «There’s no room for you.»

They didn’t mean no space. They meant, «Not you.»

The next morning, my husband got home. Abby was still asleep. I told him what happened.

He stood there for a long moment, then said, «So what do we do now?»

I didn’t answer. Not yet. But I already knew. Because there’s turning the other cheek, and then there’s turning away a 16-year-old who just wanted to be included. And they chose the latter.

I didn’t make a scene. I did this instead. Two weeks later, my parents got a letter. And started screaming.

I don’t remember the first time I got called «the weird one.» Probably before I knew what the word meant. When I was six, I found a dead bird and asked if I could dissect it. Not to be creepy; I just wanted to understand how it worked.

My mom slapped the kitchen counter and said, «Jesus, Kate, what’s wrong with you?» My sister Janelle screamed and told everyone I was trying to build a zombie. I got grounded for scaring her.

That kind of set the tone. I loved anatomy books. I wanted a microscope for Christmas. I asked questions about blood flow at dinner.

At school, I was the one who actually raised her hand. In my family, that was enough to get you labeled a show-off.

Nobody else went to college. Most didn’t finish high school on the first try. I was the only one who studied during commercials. Or at all.

By the time I was 12, my dad had started joking, half-joking, that I wasn’t really his. «Too smart to be mine,» he’d say. Then he’d laugh.

Once, I overheard him arguing with my mom when they thought I was asleep. He asked if she’d ever cheated on him. He said he «always wondered,» because I didn’t look like anyone in the family.

I didn’t sleep much that night. I never asked about it. Still haven’t.

By high school, Janelle had perfected her role as the golden child. She was loud, likable, and average in school, but excellent at turning every failure into a story. People loved her.

She knew how to cry on cue and made sure everyone knew she «watched out for me,» the poor awkward one who couldn’t take a joke. She used to call me «Dr. Freak» in front of people.

When I actually became a doctor, she upgraded it to «Dr. Moneybags.» So, progress?

When I got the scholarship—the full ride—my parents were weirdly quiet. No celebration, no hug. My mom asked who I thought I’d end up marrying, since guys don’t like women who act smarter than them.

I told her maybe I’d marry myself. She didn’t laugh.

They didn’t give me a cent. I waited tables through med school, took shifts no one wanted, and came home with sore feet and burnout in my bones. Meanwhile, my family thought I was living the dream. They didn’t visit once.