The follow-up call arrived two days later, mid-morning. I had just settled at the table with a bowl of oatmeal, still in my house slippers. The phone vibrated on the counter once, then a second time. I let the first call go to voicemail. When it rang again immediately, I answered.

Ethan’s voice was even smoother this time, almost unnervingly careful. He said he was just checking in, wanted to see how I was doing, and then casually asked if I’d had a chance to review the paperwork. I told him that I had. My own tone was flat, steady. He paused for a fraction of a second too long before saying there was no real rush, but that it would be wise to get everything in order. «Just in case,» he added.

— «What exactly do you mean by that?» I asked.

He began to ramble about the importance of planning, of being practical, of protecting me. But his words were circular, evasive. He recounted an anecdote he’d heard on the news about a woman who was locked out of her own bank accounts after suffering a stroke. Then he mentioned a friend’s mother who had forgotten all her online passwords for months. I could hear the subtext clearly. It was a curated list of justifications rooted not in genuine concern, but in cold strategy.

When I offered only silence in response, he cleared his throat.

— «I just want what’s best for you, Mom,» he said. Then his voice changed, a subtle edge of impatience creeping in. «If you wait too long, it might become more complicated to get this all set up. You really should be thinking ahead. The smart move would be to sign it now, while everything is still simple.»

As he spoke, I gazed out the kitchen window. The trees in the yard stood bare against the gray sky. A squirrel scampered across the lawn, froze for a moment, and then darted into a thicket of overgrown bushes. I watched it vanish and felt a sharp, clarifying resolve settle in my chest.

— «I’ll think about it,» I told him.

He said that was fine. Then, as an afterthought, he added that Chloe had found a highly recommended financial advisor who could help make the entire process «smoother.» He said they would be happy to arrange a meeting for me.

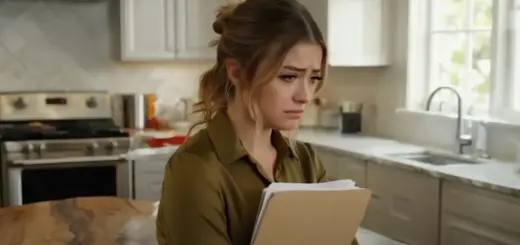

We disconnected the call. I remained seated for a long time, the oatmeal in front of me now a congealed, unappetizing lump. I felt paralyzed. I thought about all the nights I had sat by Ethan’s bed when he was sick with a fever. I remembered the time I drove five hours through a blizzard just to bring him a spare car key. I hadn’t done those things out of obligation. I had done them out of love. Because that was my definition of what it meant to be a mother. And now, here he was, speaking to me as if I were not his mother, but a transaction. A logistical problem to be solved.

The house suddenly felt claustrophobic, the silence suffocating. I got up, scraped the uneaten oatmeal into the sink, and ran the faucet until every last trace was gone. Then I went to the drawer beside the refrigerator, retrieved the manila envelope containing the documents Robert had left for me, and simply held it. It didn’t feel like a shield. Not yet. It felt like the final, sturdy piece of a foundation he had built for me. And I knew it was now my turn to build something for myself. Not from a place of anger, but from the quiet, firm realization that even a mother’s love has its limits. And I had finally reached mine.

It took me three full days to formulate my plan. Not because I was plagued by indecision, but because I needed the ensuing silence to be meaningful. I refused to let my next action be dictated by fear or wounded pride. I wanted it to be born of pure, unadulterated knowledge—an understanding of what was being demanded of me, and what I could no longer, in good conscience, permit.

I located Judith’s phone number on the back of an old Christmas card. She had been a formidable trust and estate lawyer before her retirement. We hadn’t spoken in several years, not since her own husband had passed. But I distinctly remembered something she had said to me once: «Eleanor, the quietest women often leave the most indelible marks.»

When I called, she answered on the second ring. Her voice had aged, but it retained its characteristic sharpness. I explained the situation, and she listened without interruption or judgment. When I had finished, she spoke.

— «We should meet. Let’s have coffee and find some clarity.»

The following afternoon, we sat at her small kitchen table. Her home was modest and immaculate, filled with handmade quilts and towering stacks of books. I handed her the envelope from Robert’s lockbox. She scrutinized every document, her eyes moving with the practiced efficiency of a woman who had seen too many devastating truths revealed in fine print, often far too late.

When she was done, she looked directly at me.

— «You have more power than you realize, Eleanor,» she said. «The money is secure, the investments are sound, and your legal standing is absolute. But it will only remain that way if you ensure it.»

She asked if I wished to establish a trust. I said yes. She asked whom I wanted to name as a trustee.

— «No one,» I replied. «Not yet. Maybe never.»

She gave a slow, understanding nod. Then she told me to show her the documents Ethan had given me. I produced the packet from my handbag. She leafed through the pages, her expression unchanging.

— «The language in here is predatory,» she stated flatly. «Immediate authority, sweeping access, and absolutely no oversight. These were not drafted to care for someone, Eleanor. These were drafted to absorb them.»

Together, we rewrote everything. We transferred every last asset into a private, irrevocable trust under my sole and absolute control. We fortified its access with conditions that no one could circumvent. Judith added a stringent medical clause that would require the written confirmation of two independent physicians to declare any loss of capacity before a successor trustee could be considered.

Then, she handed me a pen. I signed my name slowly, deliberately. Not because I felt hesitant, but because the act felt like drawing a definitive boundary that I should have established years ago. It was a simple line of ink on paper that declared: I am not invisible. I am not a convenience. I am not yours to manage.

When we were finished, Judith placed all the new documents into a thick, official-looking folder. She advised me to keep it in a place that was accessible but not obvious. I went home and put it in the back of the cabinet under my kitchen sink, tucked behind a bulk box of dishwasher pods that no one ever had a reason to touch.

Driving home that day, the very air seemed to have changed. It felt sharper, more vibrant. Not lighter, exactly, but clearer. It was as if I could finally perceive the true shape of my own life without having to squint. And for the first time in a very long time, I did not feel like someone’s forgotten mother. I felt like a woman with a spine. And a choice.