My name is Victor Hale, 55 years old, lead systems engineer at Veltria Housing for 18 years. I’d built their entire infrastructure from scratch, architected every expansion, kept everything running so smoothly that the executives forgot how much the company depended on me. Until they decided they couldn’t afford me anymore. I sat across from Graham Vickers, the new chief technology officer who’d been with the company for all of six months.

He was 42, wore designer glasses, and had an MBA from Cornell. He’d been brought in to modernize operations, which apparently meant cutting the most experienced staff first. The severance package is generous, said Diane from Human Resources, sliding a folder across the table.

Two months’ salary, plus your accrued vacation time. I nodded, took the folder and said, thank you. Is that all you have to say? Graham looked almost disappointed.

Maybe he’d expected me to argue or threaten legal action. Give him something to tell the board about how difficult I was being. What would you like me to say? Most people in your position have questions, concerns.

I shrugged. Seems pretty straightforward to me. Graham exchanged glances with Diane, who looked equally perplexed by my calm.

What they didn’t understand was that I wasn’t calm. I was just done. There’s a difference.

Well, we’d appreciate your help with the transition, Graham continued. The new engineering team will need some guidance on the system architecture. Perhaps a consulting arrangement for a few weeks? I’ll think about it, I said, knowing I wouldn’t.

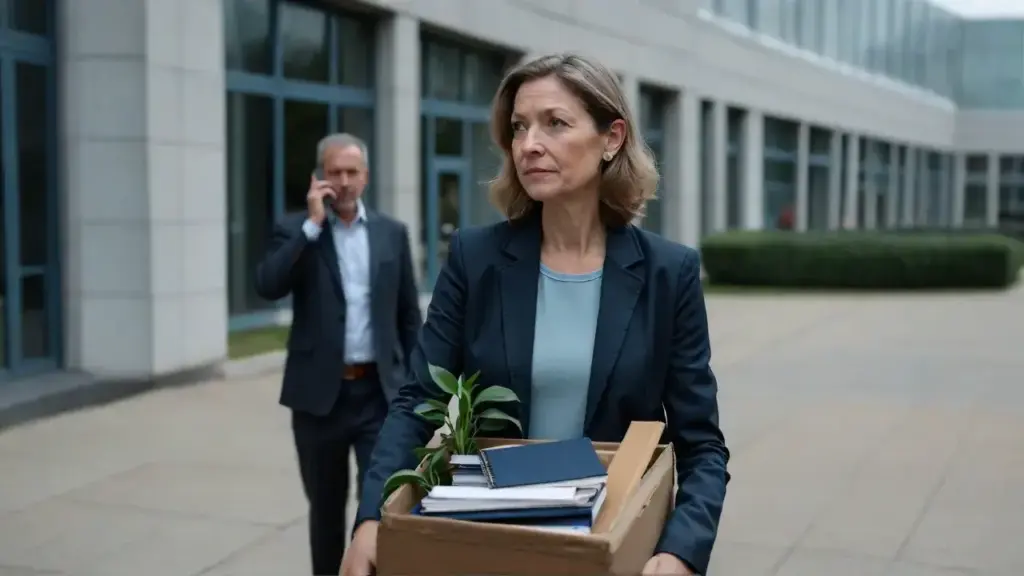

We shook hands. I cleared out my desk without complaint. Eighteen years of work fit into a single cardboard box.

I nodded goodbye to a few colleagues who looked away awkwardly, afraid the same fate awaited them. As I walked to my truck in the parking garage, my phone buzzed. A text from Alan, the database administrator I’d hired twelve years ago.

This is bullshit, Vic. The whole team’s freaking out. I didn’t respond.

At home, I sat on my deck overlooking Lake Ontario, nursing a glass of bourbon, watching the sunset paint the water copper. My wife Elaine placed a hand on my shoulder. What will you do now? I shrugged.

Something will turn up. What Graham didn’t know, what he hadn’t bothered to learn, was that I hadn’t just built their systems. I had custom-coded large sections myself, with minimal documentation, because the company had always refused to fund a proper documentation team.

Only I understood the deep redundancies, the hidden security layers, the intricate network architecture. And I wasn’t planning to explain it to anyone now. I started at Veltria Housing back when it was called Bayview Properties.

A small real estate management firm with four apartment complexes and a dozen employees. Their entire IT infrastructure consisted of two desktop computers, a fax machine, and a dial-up internet connection. The owner, Harold Bayview, hired me away from a consulting gig in Syracuse.

We’re expanding, he told me. Need someone who can build us something solid. Over 18 years, I’d turned that rudimentary setup into an integrated property management system that handled everything from tenant applications and background checks to automated maintenance requests and rent collection across 63 properties in four states.

I’d built it piece by piece, adapting, upgrading, refining as the company grew. When Harold retired five years ago, his son Justin sold the company to a private equity firm that rebranded it as Veltria Housing. They kept me on, impressed by what I’d built.

But things began to change. New executives, new priorities. Quarterly targets became more important than long-term stability.

My warning signs came gradually. First, they rejected my proposal for a documentation team. Too expensive, they said.

We’ll get to it next quarter. That quarter never came. Then they started bringing in consultants.

Young MBA types who talked about disrupting property management and leveraging cloud solutions. They’d sit through my explanations of our system architecture with glazed eyes, then recommend off-the-shelf solutions that wouldn’t integrate with our custom infrastructure. I kept pushing back, explaining why their approach wouldn’t work, showing them the custom code that made our system unique.

Eventually, they stopped inviting me to planning meetings. Elaine noticed it before I did. They’re pushing you out, she said one night over dinner.

You need to prepare. I brushed her off. They need me.

No one else understands how the whole system works together. That might be exactly the problem, she replied. Six months ago, they hired Graham as the new CTO.

He came from a banking software company and immediately started talking about standardization and legacy system replacement. He hired three junior engineers fresh out of college, had them shadowing me, asking questions about the system. I answered their questions, but I knew they weren’t grasping the complexities.

How could they? It had taken me years to build those systems, to understand the interdependencies, to create the redundancies that kept everything running smoothly when problems arose. Last week, Graham stopped by my office. Quick meeting tomorrow morning, he said casually.