She gave away more than half before finally taking a bite herself. Richard sat quietly, watching as the children around her cheered her on, their laughter filling the space. Sophie’s restaurant had become real, not because of the food, but because of the joy she carried with her. He realized that what he had brought wasn’t just lunch; it was dignity. The ability to belong without hiding.

When the other children returned to their tables, Sophie leaned forward, her voice lowering. «My mom says not to take things from strangers,» she admitted, «but you don’t feel like a stranger.»

Richard’s throat tightened. He kept his voice gentle. «Your mom sounds like someone very wise.»

«She is,» Sophie said quickly. «She used to work at a big factory in Florence. She made clothes. She worked a lot, but then they said they didn’t need her anymore. She cries sometimes, but she tells me it’s going to be okay.»

Sophie looked down at the sunflower box, her small fingers tracing its edges. «That’s why I had to pretend yesterday. I didn’t want anyone to know.»

Richard froze. Florence. He knew that factory. It was one of his own holdings, a textile company he had acquired years ago. His mind reeled as he remembered the quarterly reports, the restructuring orders, the layoffs. The name Martinez had never crossed his desk, but the decision that had uprooted her life had passed through his hands.

He felt the air leave his chest. For a moment, he wanted to excuse himself, to push the thought away as coincidence, but Sophie’s eyes were fixed on him with the kind of trust that allowed no room for denial.

He nodded slowly. «Your mom must be very strong,» he said softly.

Sophie grinned. «She is. She tells me to keep drawing and to keep smiling. She says tomorrow will always come.»

From her backpack, she pulled out a folded piece of paper and handed it to him. It was a drawing done in bright colors: three people sitting at a table together, eating. A woman with long dark hair, a little girl with braids, and a tall man in a suit.

«This is me and Mama,» she explained, pointing to the first two figures. Then she tapped the man in the suit. «And that’s you. You came to dinner.»

Richard stared at the drawing for a long time. Something inside him cracked open. He had spent his career erecting walls between himself and the people affected by his decisions. Numbers and projections had always insulated him from names and faces. But here, in a child’s drawing, he saw himself not as a distant executive but as family.

«Do you want me to keep this?» he asked carefully.

«Yes,» Sophie said, «because if you keep it, then you have to come back. Otherwise, it won’t be true.»

He folded the paper with care and slipped it into his jacket pocket. «Then I’ll come back,» he promised.

The bell rang again, and Sophie packed up her new lunchbox, clutching it tightly as if it were a treasure. Richard walked her to the classroom door. Other parents waited in the hall greeting their children, but Sophie walked alone. She turned once more to him before disappearing into her class. «Don’t forget,» she said firmly.

Richard left the school with the drawing pressed against his heart. He had entered this place intending to give a small gift. Instead, he had walked out carrying a responsibility he could not ignore. The echo of her words, That’s you. You came to dinner, followed him all the way back to his car.

As the driver opened the door, Richard hesitated. For the first time in years, his next move had nothing to do with profit or prestige. It had everything to do with a little girl who believed that tomorrow could be better and who had trusted him to be a part of it.

Richard Cole had never walked through the narrow alleys of Florence with a sense of dread before. He had visited the city for board meetings, for dinners in ornate halls, and for photo opportunities that painted him as a man of vision. But this time was different. This time, he wasn’t stepping into a villa or a hotel suite; he was following a seven-year-old girl to a small apartment above a shuttered bakery.

The stairwell smelled faintly of damp stone and old bread. Sophie climbed quickly, her sunflower lunchbox bouncing at her side. Richard followed more slowly, his polished shoes echoing in the narrow corridor. She stopped at a door with peeling paint and pressed her ear against it before turning the handle.

«Mama,» she called softly, «I’m home.»

The apartment was barely larger than one of Richard’s guest bathrooms. A small bed stood in the corner, a thin blanket folded carefully across it. A hot plate sat on a counter beside a cracked sink. The light came from one window, its curtain faded and patched. On the table lay a stack of unopened envelopes, their red lettering visible even from where he stood: overdue bills, warnings, final notices.

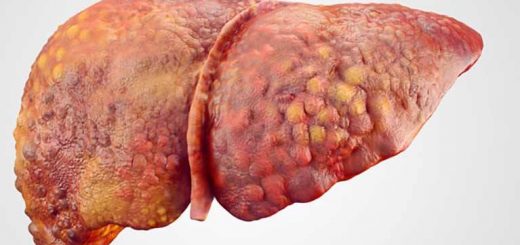

Sophie set her lunchbox down and hurried to the figure lying on the bed. Isabella Martinez was not old—mid-thirties, Richard guessed—but illness and exhaustion had carved deep shadows beneath her eyes. She turned her head slowly, revealing sharp cheekbones and lips pressed tight with determination. Even in her frailty, there was a kind of strength that commanded respect.

«This is Mr. Cole,» Sophie announced proudly, as though introducing royalty. «He’s the one who brought me the new lunchbox.»

Isabella pushed herself up against the pillow, her movements deliberate, betraying fatigue she tried to hide. «Mr. Cole,» she said quietly, her accent soft but clear. «I don’t know what to say. My daughter doesn’t usually bring home strangers.»

Richard inclined his head, unsure of how to respond. He felt like an intruder in this room, where every corner spoke of survival. «Your daughter is extraordinary,» he said at last. «She’s… she has a way of making the world brighter.»

Isabella’s lips curved into a faint smile. «She has carried more than a child should, but she keeps us both standing.» Her eyes shifted to Sophie, who was unpacking her drawing supplies onto the floor as if nothing in the world was wrong.

Richard hesitated before speaking again. «Sophie told me you worked in Florence, at the textile factory.»

For the briefest moment, something flickered across Isabella’s face: pain, pride, maybe both. «Yes,» she said simply. «I worked there for eleven years. My mother worked there before me. We thought it was secure. But then the orders slowed, the manager said costs were too high, and one day they gathered us in the break room. They read names off a list. Mine was one of them.»