My Son Laid a Hand on Me. The Next Morning, I Served Him Breakfast… And Justice

She completely ignored Jeremiah’s presence, as if he were an unimportant piece of furniture. She walked with her usual elegance to the dining room table. Her low-heeled shoes made a soft, determined sound on the wood floor.

She didn’t go to the place I had set for her, to my right. No, she went straight to the chair at the head of the table, facing me—the chair Jeremiah had just abandoned, the chair that, by right and tradition, belonged to the head of the family, my Robert’s chair. She pulled out the heavy wooden chair with a smooth movement, the scraping sound echoing in the room.

She sat down. She straightened the jacket of her linen suit. She placed her leather purse on the floor beside her. And then, she looked at Jeremiah.

Just looked. There was no anger in her gaze. No pity. There was only the weight of sixty years of friendship with me, and the weight of a lifetime spent upholding the law. It was a look that stripped the soul bare.

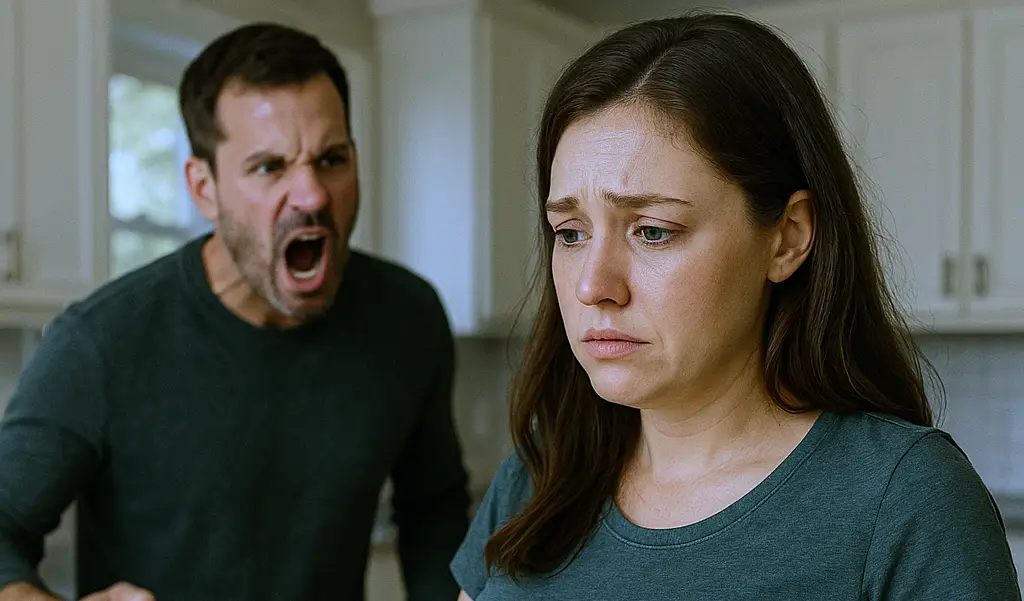

Under that gaze, Jeremiah seemed to shrink. The big, imposing man who had thrown me against the wall hours before now looked like an awkward, frightened boy, lost in a grown-up’s living room. Detective David and the other two officers remained standing in the doorway, positioned strategically.

They didn’t say a word. They didn’t need to. Their presence, the dark blue uniforms, the belts with their holstered weapons, it all spoke for itself. They were the consequence, the physical and legal answer to the violence of the night.

Mrs. Bernice, still without taking her eyes off my son, reached out and took the porcelain coffee pot. «This coffee smells wonderful, Gwendolyn,» she said, her voice calm and velvety, as if she were commenting on the weather at an afternoon tea. She poured herself a cup, the dark, steaming liquid filling the white china.

She took the small cream pitcher and added a drop. She stirred the coffee with a silver spoon, the gentle clinking of metal against porcelain cutting through the tension. She took a sip, and then she placed the cup back on its saucer with calculated delicacy.

Finally, she spoke to Jeremiah. «Jeremiah,» she began, and her voice was low, but it carried an authority that filled every corner of the room. «I remember when you were just a little boy. You used to come running to my fence, a dandelion in your hand, and say, ‘Look, Aunt Bernice, a flower for you.'»

Jeremiah swallowed hard. His Adam’s apple bobbed.

«I remember,» she continued, «you carrying my grocery bags from the market even when they were almost bigger than you were. You were such a polite boy, so kind. ‘Let me get that, Aunt Bernice. You shouldn’t be straining yourself.’ That’s what you always used to say.»

She paused, taking another sip of coffee. Every word she spoke was a small blow, a reminder of the man he should have been in stark contrast to the man he had become. It wasn’t an accusation. It was a eulogy.

«Your father,» she said, and Robert’s name seemed to hang in the air, «would have been so proud of that boy. The boy who became a man, went to college, the first in the family, the pride of our community, the pride of his mother.» She paused and glanced at me. Then her eyes returned to Jeremiah, and the softness in her voice was gone replaced by a blade of steel. «Where did he go, Jeremiah? Where is that man?»

Jeremiah opened his mouth. A hoarse sound, a groan, escaped. «Aunt Bernice, I… I don’t know what you’re talking about. This is just, um, a family misunderstanding.»

It was the wrong thing to say. Mrs. Bernice’s eyes narrowed. «A family misunderstanding,» she repeated, her voice dripping with irony. She gestured with her chin in my direction. «Look at your mother’s face, Jeremiah. Look closely. That on her lip, the bruise forming under her eye, does that look like a misunderstanding to you?»

He couldn’t look. His eyes fell to the floor, to the crumbs of the biscuit he had dropped.

«No.» Mrs. Bernice’s voice was sharp now. «That has a name, and we both know what it is.»

That was Detective David’s cue. He stepped forward, pulling a small notepad from his uniform pocket. His presence was imposing. He looked at Jeremiah with an expression of profound disappointment.

«Jeremiah Hayes,» David said, his voice grave and official, without the warmth of Brother David from church. «We’ve received multiple complaints of disturbing the peace from your neighbors over the last six months. Loud noise, late-night music, shouting.»

Jeremiah hunched his shoulders, still staring at the floor.

«We also have a record,» the detective continued, flipping a page in his notepad, «of an altercation at the Salty Dog Bar three weeks ago. You were involved in a fight and had to be restrained by security. You were released with a warning.»

Jeremiah’s head came up a little, surprised that he knew about that.

«And we have two reports, not yet confirmed by a traffic stop, of you driving recklessly after leaving said bar. In short, Jeremiah, you’ve been on our radar.» David paused, and his gaze grew even more serious. «And then this morning, at 4:37 a.m., I received a phone call, a domestic assault complaint, from this address. The victim, your mother, Gwendolyn Hayes.»

Every word from the detective was a nail being hammered. The list of his failures, his transgressions, being read aloud in his childhood dining room, in front of the woman who was a second mother to him. The humiliation was palpable.

The air was thick with it. I stood up. All eyes turned to me. My back was aching, but the back support belt I’d put on under my dress kept me upright. I would not falter. Not now.

I walked slowly around the table until I was standing next to Mrs. Bernice’s chair. I placed my hand on her shoulder, and I felt the solidity, the support. And then, I looked at my son. Not at the floor. Not at the wall.

Straight into his eyes. And for the first time in a very long time, I was the one who made him look away. «Jeremiah,» I began. My voice was calm, but there was no warmth in it. It was the voice of a woman who had walked through hell during the night and come out the other side.

I needed him to understand. This wasn’t about hate. It was about something much more complicated. I’d put on lipstick before coming downstairs. A wine-colored lipstick, real dark, with a matte finish.

My niece had sent it to me as a gift. She said it was long-lasting, that it wouldn’t even come off if you drank water. I put it on that morning for a reason. I didn’t want them to see my lips tremble. I wanted my mouth to be firm, strong, when I delivered his sentence.

«I didn’t call them here out of hate, Jeremiah,» I said, the color of the lipstick making every word stand out. «I called them because I love you.»

He snorted, a sound of scorn. «You love me? You call the cops on someone you love?»

«Sometimes,» I replied, without blinking. «Sometimes, the greatest act of love isn’t protecting someone from the consequences of their actions. It’s delivering them to them.»

The room fell silent again. The only thing moving was the steam rising from the coffee cups, like souls ascending to heaven. The trap was set. The witnesses were in place. The law was present. And now, it was the victim’s time to speak.

Jeremiah’s scornful laugh hung in the air for a second, thin and brittle, before it died under the weight of my gaze. «You call this love?» he repeated, his voice rising an octave, bordering on hysterical. «This is betrayal. You’re turning me over to strangers. This is a family matter, Mom. Our business.»

«No, Jeremiah.» Mrs. Bernice’s voice cut through the air, cold and precise as a scalpel. She didn’t even bother to look at him. She continued to sip her coffee, as if discussing a trivial matter of gardening.

«It stopped being a family matter the moment you raised your hand to the woman who gave you life. At that instant, it became a community matter, a legal matter. And if I may say so,» she finally set her cup down and fixed her eyes on him, «it became my matter.»

The power in those last words silenced Jeremiah instantly. Arguing with me was one thing. Arguing with Judge Bernice Johnson was something else entirely. He shut his mouth, his face twisted in a mixture of anger and fear.

I remained standing next to Bernice, my hand still on her shoulder. I felt as if I were drawing her strength, her courage. I looked at my son, the frightened man-child across the table, and the torrent of words I had held back for two years finally found a way out.

«A family matter,» I repeated, my voice low, but every syllable weighted with pain. «You want to talk about family, Jeremiah? Let’s talk. Family is your father, Robert, working from sunup to sundown at that port, his hands covered in calluses, his back aching to make sure you had books for school and food on this very table. That’s family.»

I took a step, moving around Bernice’s chair, getting a little closer to him. «Family, my son, is me, after your father was gone, working as a seamstress until my fingers bled and then going to clean floors in an office downtown, coming home in the dead of night just to make sure your college tuition was paid, to make sure you’d have a better future than we did. That’s family.»

He shrank back in his chair, unable to meet my gaze. «And you?» I continued, my voice beginning to tremble, not with weakness, but with a righteous anger finally breaking free. «What did you do with this family? You took your father’s sacrifice and my sacrifice, and you spat on it. You took the pain of your demotion, your frustration, your inability to deal with life’s problems like a man, and you turned it into a weapon.»

«And you aimed that weapon at me,» I said, «the only person in the world who never, ever gave up on you.» The tears began to stream down my face, but I didn’t care. I didn’t wipe them away. I let them fall, like liquid witnesses to my pain.

«Night after night, Jeremiah. Night after night, I sit in that kitchen and I pray. But my prayers have changed. I used to pray for your safety, for your success. Now I pray that you come home and go straight to bed without speaking to me. I pray that your poison won’t touch me. I pray to be invisible in my own home. You have turned my home into a prison. You have turned my mother’s love into a sentence.»

«I… I didn’t mean to hurt you,» he stammered, finally looking up. There were tears in his eyes too, but they were the tears of self-pity. «I drank too much. I lost my head. It won’t happen again, Mom, I swear. I swear to God.»

«Oh, no, no, no,» I said, shaking my head slowly. «Don’t you use God’s name in this house. Not today. How many times have I heard that promise, Jeremiah? Huh? How many hungover mornings have you woken up crying, begging for my forgiveness? And I, like a fool, believed you. Every single time. I forgave you. I cleaned up your messes. I lied to the neighbors. I hid my tears. I protected you.»

«And you know what my forgiveness did? You know what my protection did?» I leaned over the table, my knuckles resting on the lace tablecloth. «It gave you permission. My silence, my forgiveness… they told you it was okay, that you could yell, that you could break things, that you could humiliate me. And last night, they told you that you could hit me.»

The word hit hung in the air, ugly and irrefutable. «And you know what the worst part is, Jeremiah?» I went on, my voice now a hoarse whisper. «It wasn’t the pain. The physical pain goes away. The bruise will fade. The lip will heal. The worst part was your silence afterward. The way you turned your back and went upstairs like you’d just stepped on a bug. Your total and complete lack of remorse.»

«It was right there in your silence that I understood. I understood that I wasn’t dealing with my son having a bad day anymore. I was dealing with a man who took pleasure in inflicting pain on someone weaker, and that person was me.»

I straightened up. I glanced at Detective David. His face was impassive, but I saw the pain in his eyes. He was a father of two girls. He understood.

«I carried you for nine months, Jeremiah,» I said, turning my gaze back to my son. «I raised you. I gave you my life, and my mother’s love is the strongest thing I have, but my love does not require me to be your punching bag. My love does not require me to be an accomplice to your destruction, and protecting you from yourself at this point is exactly that. It’s helping you destroy yourself and taking me down with you.»

He started to cry for real now. Loud, childish sobs. «Mom, please, don’t do this. I’ll go to rehab. I’ll stop drinking. I’ll go back to church. Anything, but don’t let them take me, please. It’s a family matter.»

«The law is clear on domestic assault, Jeremiah,» Detective David’s voice sounded, calm but final. «It’s not something we can ignore.»

«What will the neighbors say?» he whimpered, in a last, pathetic attempt to appeal to my shame.

That’s when I picked up my watch, a gold wristwatch, small and delicate, that used to be my Robert’s. I wore it every day. I looked at the time: 8:15. I looked at him and said, «I don’t care what the neighbors will say anymore. I’ve spent the last two years caring about that, and look where we are. From today on, I only care about one thing: my peace. And my peace, Jeremiah, begins with your absence from this house.»

I sat down in my chair again. I picked up my linen napkin, and with perfectly steady hands, I served myself a spoonful of grits. I wasn’t going to eat, not really. My stomach was a knot of anguish, but the act, the act was symbolic. I was taking back my life, my table, my house.

Mrs. Bernice, seeing my gesture, nodded slowly. She turned to Jeremiah, his face a mess of tears and snot. «Your tears don’t move me, boy,» she said, her voice without a shred of sympathy. «An abuser’s tears are always about himself, never about the pain he’s caused. Your mother, by doing this, is giving you the only chance you have: the chance to face the man in the mirror without the excuse of the bottle, without the shield of her easy forgiveness. She is forcing you to grow up. And that, Jeremiah, is the greatest, most painful, and truest act of love you will ever receive.»

She turned to Detective David and gave a slight nod of her head. It was the signal. The trial at the dining room table was over. The sentence was about to be carried out.

Mrs. Bernice’s nod was almost imperceptible, but to Detective David it was as clear as the sound of a judge’s gavel. He put his notepad away in his uniform pocket, and the small gesture marked the end of the conversation and the beginning of the action. He took a step forward, fully entering the dining room.

The younger officer, who had been posted near the door, followed him. The air in the room, which was already heavy, became thin. I felt my chest tighten. It was real. It was happening.

«Jeremiah.» Detective David’s voice was formal, devoid of any warmth. He was no longer Brother David from church. He was the law. «Please stand up and place your hands behind your back.»

Jeremiah’s crying stopped abruptly, replaced by a look of panic and disbelief. He looked from David to me and back to David. «You can’t be serious,» he stammered. «David, for God’s sake, you’ve known me since I was a kid. You saw me get baptized, and you’re going to arrest me in my own house, in front of my mother?»

«I’m arresting you because of your mother, Jeremiah,» David replied, his voice firm, unwavering. «And because the law requires me to. Now please, don’t make this any harder than it already is.»

The second officer moved up behind Jeremiah’s chair. The movement was what finally seemed to break my son’s trance. The panic turned to rage. He shoved his chair back with a loud bang and jumped to his feet, his face red with anger.

«Don’t you touch me!» he yelled, pointing a finger at the officer. «This is absurd. It’s a family matter. She’s my mother. We fight sometimes. Everybody fights.» He turned to me, his eyes pleading and furious at the same time. «Mom, tell them. Tell them to stop. It was just an argument. I lost my head. Tell them you don’t want to press charges.»

Everyone in the room looked at me. His question hung in the air. The last chance for me to back down, to go back to being the protective mother, the fearful woman. For a second, my heart faltered.

To see my son, my baby, in this situation, cornered, desperate. It was the hardest thing I’ve ever had to endure. I was holding a scarf in my hand, a silk scarf with a magnolia print that Robert had given me. I had grabbed it from my dresser before coming downstairs, anticipating tears, and now I was clutching it so tightly in my hand that my knuckles were white. The thin fabric was soaked, not with the tears I’d shed, but with the ones I’d held back.

I looked at Jeremiah, at his contorted face, and I found my voice. «I’ve said everything I have to say, Jeremiah.» My voice came out low, but clear. «I’m not going to lie for you. Not anymore.»

Those words were the final sentence. Jeremiah’s face crumbled. The anger gave way to abject despair. He seemed to deflate, as if his spine had been removed. He knew he had lost.

«Please,» he whispered, his voice broken. «Don’t do this.»

Detective David didn’t wait any longer. With a swift, practiced move, he took Jeremiah’s arm and turned him around. The younger officer took the other hand, and then I heard the sound, the metallic, dry sound of steel teeth locking together. Click.

The sound of handcuffs, the sound of freedom for me, and the sound of rock bottom for him. Jeremiah let out a sob, a guttural sound of pure defeat. He didn’t resist anymore.

He just stood there, his head bowed, his shoulders slumped, as Detective David read him his rights. «You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law.»

The detective’s voice was a monotone drone, the familiar litany I’d only ever heard in movies and on television. To hear it in my own dining room, being read to my own son, was surreal. Mrs. Bernice didn’t move. She remained seated, a silent and regal witness, her presence an anchor of dignity in the chaos of my life. She was the proof that I wasn’t crazy, that I wasn’t overreacting.

They started to escort him out of the room. As Jeremiah passed by me, he stopped for an instant. He lifted his head and looked me in the eye. His face was wet with tears.

«Mama,» he began. I thought he was going to apologize. But no.

«You’re going to regret this, Mama,» he said, his voice low, full of a poison that chilled my blood. «You’re going to be all alone in this old house with your old junk, and you’re going to regret it.»

It was a threat, the last attempt of a tyrant to maintain control through fear. But the fear in me had died that morning. I met his gaze without flinching. I didn’t feel anger. I felt nothing but a deep, abysmal sadness. And pity. Pity for the weak man he had become.

«Maybe, Jeremiah,» I replied, my voice steady without a hint of hesitation. «Maybe I’ll regret that it had to come to this. But I will never, ever regret choosing my own life today.»

Detective David gently pulled him by the arm, and they continued walking. I watched them as they crossed the front hall. The other officer opened the front door. The bright morning sun flooded the hallway, making me blink.

I didn’t go to the door. I didn’t want to see the curious neighbors peering out their windows. I didn’t want to see the look on my son’s face as he was put into a police car. I stood just inside my dining room and just listened.

I heard their footsteps on the wooden porch. I heard Detective David’s voice saying something to him. And then I heard the sound of the police car door slamming shut. A hollow, final sound.

And then the sound of the engine starting and driving away until it faded into the distance. And then the silence returned. But it was a different kind of silence.

It wasn’t the heavy, oppressive silence of the early morning. It was a light silence. Empty, yes. Painful, without a doubt. But light. It was the silence of peace. The silence of a house that no longer held fear.

I just stood there for I don’t know how long. My muscles, which had been tense for hours, began to relax. The adrenaline that had kept me on my feet started to dissipate and a wave of exhaustion, so overwhelming, hit me.

My knees buckled. Before I could fall, I felt a firm hand on my arm. It was Mrs. Bernice. She had gotten up and come to me. She held me steady and the other officer, the one who had stayed behind, came over and pulled out a chair for me.

Bernice helped me sit down. «It’s over, Gwen,» she said, her voice soft for the first time that morning. «It’s over.»

And it was only then, sitting there in my dining room, with the smell of coffee and biscuits still in the air, with my best friend beside me, that I allowed myself to fall apart. I covered my face with my hands and I wept. I wept for the loss of my son, for the shame, for the pain. I wept for the boy he once was and the man he never became. I wept for the loneliness that lay ahead of me and I wept too for the terrifying relief of being finally and absolutely free.

The days that followed Jeremiah’s arrest were the strangest of my life. The house suddenly felt enormous, cavernous. Every creak of the floorboards, every tick of the clock echoed in the emptiness he’d left behind. At first, I kept expecting to run into him around a corner.

I’d expect to hear his heavy footsteps on the stairs, the sound of the TV turned up too loud on the sports channel, but there was nothing, just silence. A silence that, for the first few days, was as deafening as his yelling had been. Mrs. Bernice and my sister Paulette, who arrived from Atlanta that same afternoon, formed a one-woman army around me.

Paulette cleaned up the mess in the kitchen, picking up the shards of my ceramic vase with a look of quiet fury. «I’ll glue every piece back together, Gwen,» she said. «But some things, once they’re broken, are never the same.» I knew she wasn’t just talking about the vase.

Bernice, for her part, handled the outside world. She spoke to the neighbors with a short, dignified version of the facts, cutting off any gossip at the root. «Jeremiah is unwell and required a serious intervention. Gwendolyn was brave and did what had to be done. The family asks for privacy and prayers.»

The word of a retired federal judge, my dear, carries more weight than any porch gossip. They made me eat. Paulette made my favorite soups. Bernice brought over slices of sweet potato pie, but the food had no taste. I felt numb, like I was floating outside my own body, watching some sad old woman move through her house.

The hardest part was the nights, lying in my bed, in the absolute quiet of the upstairs, knowing that the room next door, my son’s room, was empty. I would imagine where he was, in a cold cell at the county jail, with strangers, with criminals. The mother in me would scream. I felt like a traitor.

I had nightmares. I dreamt he was a little boy again, crying behind bars, and I couldn’t reach him. I woke up several times with my face wet with tears. It was Bernice who, on the third day, sat with me on the porch and gave me the harshest medicine.

«Gwendolyn, stop,» she said, her voice firm, but not without compassion. «Stop torturing yourself. You didn’t put him there. His choices put him there. The liquor put him there. His anger put him there. You just opened the door so the consequences could walk in. And you only did that when your own life was at risk.»

She was right. I knew she was. But a mother’s heart doesn’t run on logic. It runs on a stubborn, sometimes blind, love.

That same week, I took the first step for my own safety. I’d always been a woman who felt safe in her home, never even locked my doors during the day. But Jeremiah’s threat at the door—»You’re going to regret this»—had lodged itself in the back of my mind.

I called a company I saw advertised online and had a security system put in. Little, discreet cameras on the front and back porches and an alarm with sensors on the doors and windows. The young technician who came to install it was very kind. He showed me how to arm and disarm the system with a small keypad by the door.

The first night, I pressed the buttons and heard the soft beep confirming the house was locked down. I breathed a little deeper. It was a small bit of control, but it was my control. My sense of security was no longer something that depended on someone else’s mood.

The second step was at the suggestion of Reverend Michael from our church. He came to visit, brought me a book of Psalms, and talked with me for a long time. «Sister Gwen,» he said, «the body heals, but the soul needs a different kind of doctor.»