My Son Laid a Hand on Me. The Next Morning, I Served Him Breakfast… And Justice

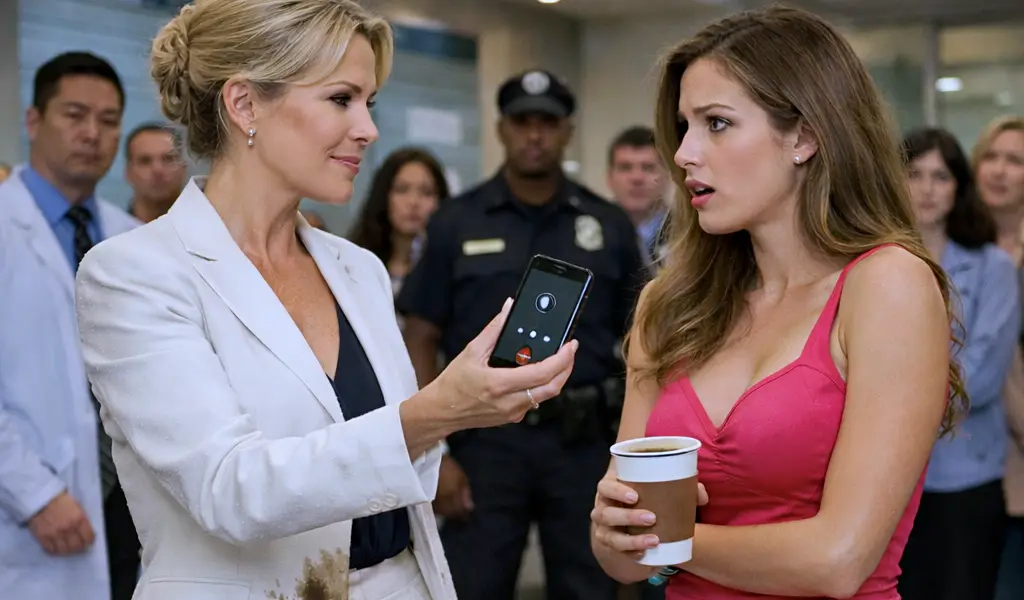

I waited, my heart hammering against my ribs. Detective David, a good man, a deacon at our church. He’d known Jeremiah since he was a boy in the choir. He’d watched Jeremiah grow, watched him become a man.

But he was also a cop, a man of the law. I wasn’t calling Brother David, the deacon. I was calling Detective Miller, the officer, and I needed him to act like one.

After a few minutes that felt like hours, David’s deep, familiar voice came on the line, thick with sleep and concern. «Sister Gwen, what’s going on? Are you safe?»

And then, for the second time that night, I had to tell it. I had to put my shame into words. «David, Jeremiah, he assaulted me. He came home drunk and he hit me.»

My voice broke on the last word. I heard a rustling sound in the background, like he was getting out of bed, pulling on clothes in a hurry.

«Where is he now, Sister Gwen? Is he still there? Do you need me to send a car right now?»

«No, no,» I said too quickly. «He’s sleeping. I’m safe for now. David, I don’t want them to come now. I don’t want a scene in the middle of the night with sirens and lights waking up the whole neighborhood. I want to do this my way, with dignity.»

He was silent, processing. I knew I was asking for something outside of protocol.

«I have a plan,» I continued. «Mrs. Bernice Johnson will be here at eight in the morning. I want you to come too, David. You and two other officers. I want you to walk in, sit down, and we’re going to handle this like civilized people. Before you take him.»

David sighed, a sigh of a man torn between his duty and his affection for my family. «Sister Gwen, that’s highly irregular.»

«I know it is, David, but you know me, you know Jeremiah. You know if a squad car shows up here with sirens blazing, he’ll react badly. He’ll fight, he’ll scream. It’ll turn into a circus. I don’t want that. I want him to look me in the eye. I want him to look Mrs. Bernice in the eye. And I want him to look you in the eye, David. I want him to understand what he’s done. I don’t want him to be just another drunk being dragged out of his house. I want him to feel the weight of his community’s disappointment. Do you understand?»

He was quiet for a long time. Then he said, «I understand, Sister Gwen. Eight o’clock sharp. We’ll be there. Just lock yourself in your room to be safe. And if he wakes up, if he tries anything, you call me immediately. Understood?»

«Understood, David. And thank you.»

«God bless you, Sister Gwen,» he said, and hung up.

Two calls made. One to go. The most personal one. I dialed the area code for Atlanta. My sister, Paulette. She picked up on the first ring, as if she’d been waiting.

«Gwen?» I felt it. «I knew it was you. What did he do?»

Paulette and I always had that connection. She knew. She always knew. I told her everything. The broken vase, the yelling, the shove, the slap.

She listened in silence, with just the sound of her breathing on the other end of the line. When I finished, she didn’t say, «I told you so.» She didn’t say, «You should have left a long time ago.»

She just said, her voice thick with anger and love, «What are you going to do?»

«I’ve called Bernice and Detective David. They’re coming at eight,» I said, my voice now sounding exhausted. «I’m turning him in, Paulette.»

A sob escaped her. «Oh, Gwen, my dear sister, I’m so sorry.»

«I know,» I said. «I just… I wanted you to know. I wanted someone in our family to know what I’m doing, so that, if I ever doubt myself, you can remind me of today, of this night.»

«I’ll remember,» she promised. «I’m getting the first bus to Savannah in the morning. I’ll be there by the afternoon.»

«Thank you. Take care of yourself, Gwen, and know this: you are the strongest woman I know.»

I hung up the phone. I placed the handset back in its cradle. The three calls were made. The three pillars of my plan were in place: moral authority, the law, and family.

I felt a deep weariness, an exhaustion that came from the soul, but at the same time, I felt light, as if a two-ton weight had been lifted off my back—the weight of silence. I looked at the clock. Almost six in the morning.

The sky outside was beginning to lighten, from a deep black to a bruised bluish gray. The storm had passed. I had two hours, two hours to finish preparing breakfast, two hours to get myself ready, two hours to prepare for the final battle.

I went to the kitchen and started making the peach preserves. Justice, after all, was going to be served, and it would have a bittersweet taste. The gray morning light started to filter through the kitchen windows, revealing the silent chaos of my vigil.

There was a dusting of flour on the floor, dirty bowls in the sink, and the sweet heavy smell of biscuits hanging in the air. The sky outside was pale, washed clean by the night’s rain. It was the calm after the storm, and I felt that same calm inside me, a strange, cold calm, but an unshakable one.

The exhaustion weighed on my shoulders like a shroud, but my mind was sharper than ever. Less than two hours to go. I needed to finish setting the stage.

It wasn’t enough to just have law and order on my side. Jeremiah needed to understand what he was losing. He needed to see, in a concrete way, the home he was destroying, the mother he was throwing away. His punishment wouldn’t just be legal. It had to be visual, emotional.

I started cleaning the kitchen with a renewed energy. I washed the dishes, scrubbing each plate and bowl with a force, like I was scouring the filth from my own soul. I dried everything and put it away.

I wiped the flour from the counter and the floor. The kitchen, in twenty minutes, was spotless, gleaming in the morning light, as if the violence and despair of the night had never happened. It was a façade, a beautiful, orderly façade, just like the life I had been leading for the past two years.

Then I turned to the food. The biscuits were already done, dozens of them, piled on a white ceramic platter. I went to the pantry and got a can of peaches in syrup. I opened it and poured the contents into a saucepan, adding some brown sugar, a dash of cinnamon, and some freshly grated nutmeg.

As the peaches bubbled on the stove, the sweet and spicy aroma mixed with the buttery smell of the biscuits. It was the smell of Jeremiah’s childhood. When he was a boy and got sick, I’d make him these same preserves to eat with toast.

He used to call it his «sweet medicine.» The irony of it. I was preparing the most bitter medicine of his life, and he didn’t even know it. While the preserves thickened, I put a large pot of water and salt on to boil for the grits—creamy grits with plenty of butter and a little bit of sharp cheddar stirred in at the end.

Soul food, food for the soul. But right then, it felt more like food for a condemned man. A last meal.

As the water boiled, I focused on an important detail: the knives. I had a set of kitchen knives Robert had given me for a birthday many years ago, but last year, the wooden handle on my favorite chef’s knife had cracked. Paulette, always paying attention, sent me a new set as a gift.

It was from some German brand, high-quality steel, and they came in a heavy wooden block. «So you can chop your collards easier, sis,» she joked. I kept them razor sharp.

I took the paring knife from that block. The blade gleamed. I used it to slice some fresh fruit to garnish the table. Strawberries, cantaloupe.

Every cut was precise, clean. I moved with the skill of a woman who’d spent her life in the kitchen. But that morning, there was something else in my movements. A surgical precision, like a doctor preparing for a delicate operation on which a patient’s life depended.

And in a way, my life depended on what was about to happen. With the food almost ready, it was time to set the table. I went to the china cabinet, the very one I’d been thrown against.

I ran my hand over the dark wood, feeling the solid texture, the history in it. I opened the glass doors carefully. The smell of old wood and beeswax filled my senses. Inside was my heritage, my wedding china, my mother’s crystal glasses.

First, the tablecloth. I went to the linen closet in the hall and took out my best one: white, pure linen with a delicate lace trim handmade by my grandmother. I used it so rarely, it still smelled of the lavender sachets I kept with it.

I spread it over the dining room table. The stark white fabric covered the dark wood, creating a shocking contrast, a blank canvas for the scene that was to come. Then, the china.

I went back to the cabinet and with reverent care took out the dinner set. Plates, saucers, cups. Each piece was white with a thin gold rim and tiny hand-painted blue flowers.

I washed them in the sink one by one to get any dust off and dried them with a soft cloth. I set four places at the table: one at the head for me; one to my right for Mrs. Bernice; one to my left for Detective David; and one at the other end, facing me. Jeremiah’s place.

I placed the silver cutlery, which I had polished the week before, next to each plate. White linen napkins, ironed crisp, folded neatly. A small crystal vase with a single white camellia from my garden in the center.

The table was set for a king—or for a sacrifice. The line between the two, I was discovering, was very thin. Everything was ready. The food, the table.

Now it was my turn. I went upstairs, the steps creaking under my feet. The upstairs hallway was dark and quiet. I walked past Jeremiah’s door.

I could hear him snoring, a heavy, guttural sound. The sound of a man sleeping the sleep of the unaware, with no idea of the earthquake that was about to shatter his life. For a brief second, I felt a pang of pity, an almost overwhelming urge to open that door, to shake him, to scream, Wake up, my son! Wake up before it’s too late!

But I didn’t. I took a deep breath and continued on to my room. I entered my sanctuary. My room was simple, tidy. The patchwork quilt I made myself was on the bed.

The white lace curtains filtered the grey morning light. I went to the bathroom and looked at myself in the large mirror. The sight was still shocking. The bruise under my eye was darker now, an ugly smudge of blue and purple. My lip, more swollen.

I needed a shower. I needed to wash the smell of fear and flour from my body. I turned on the tub faucet and let the hot water run. I added some lavender bath salts and the fragrant steam filled the bathroom.

While the tub filled, I went to my closet. I didn’t hesitate. I went straight to the back, where I kept the clothes I rarely wore, and I took out the dress.

It was a Sunday dress made of crepe in a deep, almost navy blue. It had long sleeves, a modest neckline, and fell straight to my mid-calves. It was an elegant, sober dress, the kind of dress you wear to church or to a funeral, or, as I was about to find out, to a judgment.

I took my bath. The hot water stung my bruised back, but also relaxed my tense muscles. I washed my hair, scrubbing my scalp hard. I tried not to think.

I just focused on the sensations, the water, the soap, the steam. I got out, dried myself off, and put on the blue dress. It fit perfectly.

I combed my wet hair and pinned it into a low, tight bun at the nape of my neck. I looked in the mirror again. The bruise and the cut lip stood out even more against my clean skin and the dark fabric of the dress.

And that’s exactly what I wanted. I wasn’t going to hide a thing. My wounds were my witnesses.

I sat at my vanity. I don’t wear much makeup, just a little powder and some lipstick. But that morning, I made a point of it. I dusted my face with rice powder to take away the shine.

And then, I opened the drawer and took out something I kept for special occasions. A belt. But not just any belt. It was a back support belt.

One of those ones the doctors recommend, you know. A discreet one, skin-toned, to wear under my clothes. I’d bought it online some time ago for the days when my arthritis acted up real bad.

I put it on under the dress, pulling it tight. It gave my back immediate support, easing the pain from the blow against the china cabinet and, more importantly, forcing me to keep my posture straight. I would not slouch. Not today.

I looked at the clock on my bedside table. 7:40. It was almost time. I went downstairs. The house was filled with smells and a silent expectation.

I poured the fresh coffee into a porcelain pot, the grits into a tureen, the preserves into a crystal bowl. I carried everything to the dining room table. Everything was perfect. Dangerously perfect.

I sat down in my chair at the head of the table. I smoothed the blue dress over my knees. My hands were calm now. My heart was beating in a steady, slow rhythm.

I was ready. And that’s when I heard it. The sound of footsteps upstairs. The creak of the floorboards in Jeremiah’s room. He was awake.

The guest of honor was about to come down for his feast. The sound of footsteps upstairs was unmistakable. First, the groan of the bed. A heavy, lazy sound.

Then, the shuffling of feet on the wood floor. I knew that routine by heart. It was the sound of a hangover. The sound of a man moving through a fog of headache and shallow regret.

I stayed seated, motionless, my hands folded in my lap, feeling the texture of my dress. My heart didn’t speed up. My breathing didn’t change. I was the picture of serenity, a calm statue sitting at the head of a war table.

I heard the water run in the upstairs bathroom. A quick shower. He always did that, as if water could wash away not just the grime from his body, but the filth from his soul. Foolish man. His filth was bone deep.

The footsteps started again, now coming down the stairs. One step at a time. Heavy. Deliberate. The staircase in our house is old, solid wood, and each step has its own unique groan.

I knew them like I knew the notes of a hymn. I could tell, just by the sound, where he was. Halfway down. Three steps to go. Now in the front hall.

There was a pause. I knew what he was seeing. The hall table and the broken shards of my blue ceramic vase on the floor. I hadn’t cleaned it up. I’d left it on purpose.

I wanted it to be the first thing he saw, the physical evidence of his nighttime rage. I had hoped it might bring him a sliver of shame, of remorse. But what I heard next wasn’t a sigh of regret. It was a huff, a sound of disdain.

And then I heard the sound of the shards being kicked into a corner with the toe of his shoe, carelessly, like it was just trash. In that moment, any lingering shred of pity I might have had for him evaporated. All that was left was the coldness of my resolve.

And then he appeared in the dining room doorway. He stood there, his hand on the doorframe, and blinked, adjusting to the light. The morning sun, still weak, was streaming through the large window, illuminating the set table.

He was dressed in wrinkled khaki pants and a polo shirt that had seen better days. His hair was still damp from the shower, but his face, his face was puffy, his eyes red and small. The stubble on his chin gave him an air of slovenliness, of defeat.

He took in the scene: the white lace tablecloth, the fine china, the gleaming silver cutlery, the steaming platters of food, the smell of coffee, biscuits, peach, and cinnamon. He scanned it all, and a look of confusion settled on his face. He was expecting yelling, accusations, or at best, my silent treatment, my contempt.

He wasn’t prepared for this, for this unexplainable celebration. He looked at me, and for the first time that morning, he seemed to really notice my face. I saw his eyes fix for a second on my swollen lip, on the bruise blooming on my cheek, but his reaction wasn’t shock or guilt.

It was an almost imperceptible twitch of his lips, a glimmer of satisfaction, of power. And then, the confusion on his face morphed into something else: arrogance. A slow, crooked smile spread across his face.

He had read it all wrong. In his sick mind, this feast wasn’t a trap. It was a peace offering, a white flag.

In his mind, the slap from the night before had worked. He had finally tamed me. He had put me in my place, and now, like a good, submissive mother, I was pleasing him, apologizing with food.

The sight was so absurd, so twisted from reality, that I almost would have laughed if it wasn’t so tragic.

«Well, well,» he said, his voice still hoarse from the hangover. He straightened up, puffing out his chest, and walked to the table like a king surveying his domain. «To what do I owe the honor of this grand banquet?»

I didn’t answer. I just watched him, keeping my expression neutral. My silence seemed to amuse him even more.

He pulled out his chair, the one at the opposite end from me, and threw himself into it with a thud. He picked up a linen napkin, looked at it with a fake air of sophistication, and tossed it in his lap. Then, he reached out and took a biscuit from the basket, the most perfect one, the most golden one of all.

He held it up for a moment. «I gotta admit, Mom, nobody makes biscuits like you.» And then he took a huge bite.

He ate with his mouth open, without any manners, crumbs falling from his mouth onto the pristine tablecloth. He chewed loudly, and after he swallowed, he pointed what was left of the biscuit at me.

«There you go, Mom,» he said, his voice full of that cruel victory. «See, you finally figured out who’s in charge around here, huh? A little discipline, and things fall right back into place. That’s how it’s gotta be.»

His words hit me, but I didn’t show it. On the outside, I was a statue of ice. On the inside, every word he spoke was another nail in the coffin of my old life.

He felt no remorse. He felt pride. Pride in having hurt me. Pride in having humiliated me. He believed violence was the answer.

I just stared at him from across the table. The silence stretched. He shrugged and picked up his coffee cup. He was about to pour himself some when the sound cut through the air.

Ding-dong.

The sound of the doorbell. Sharp, clear, punctual. Jeremiah stopped, his hand hovering over the coffee pot. A scowl of irritation formed on his forehead.

«Who the hell is it at this time of morning? Did you invite someone?»

«Yes,» I said, and it was the first word I had spoken that morning. My voice came out calm, steady. «I did.»

«You what?» He growled, slamming the cup down on its saucer. «I don’t want to see anyone. Send them away, whoever it is.»

I ignored his command. With a slow, deliberate movement, I placed my hands on the table, pushed myself up, and stood. I smoothed the front of my blue dress, and I walked, without hurrying, out of the dining room and toward the front hall.

«Mom, didn’t you hear me? I said, send them away!» His voice followed me, full of anger at my disobedience.

I didn’t look back. I just kept walking. My Sunday shoes made a soft sound on the wood floor. I reached the front door.

I took one last, deep breath. I looked at my distorted reflection in the glass of the door. I saw the woman in blue, with the bruised face and the posture of a queen. It was time.

I turned the brass knob and pulled the door open. The Savannah morning air drifted in, fresh and damp. On my porch stood the three people I was expecting.

Mrs. Bernice Johnson, immaculate in her peach-colored linen suit, wearing a string of pearls and a serious expression that would make any lawyer tremble. Beside her, Detective David Miller, tall and imposing in his uniform, his cap held in his hand, his face grim with concern and duty. And behind him, two younger officers, both with professional neutral expressions.

I looked at Bernice. She looked at my face, at my lip, at my eye. I saw a flash of fury in her eyes, but she controlled it instantly. She just gave me a nod, an almost imperceptible movement, but it said everything. I’m here. We’re here.

«Good morning, Gwendolyn,» she said, her voice as firm as a judge’s in a courtroom.

«Good morning, Bernice. Detective,» I said, my voice just as steady. «Please, come in. The coffee is served.»

I stepped back from the door, holding it open for them. They entered in silence, one by one. Their presence filled my small hallway. Authority, the law.

They walked behind me, toward the dining room. Jeremiah, who had gotten up annoyed to see what was going on, was standing in the doorway of the room, and that’s when his world fell apart.

When he saw the group walking in—when he saw Mrs. Bernice with her courtroom air, when he saw the uniform on Detective David and the other two officers—his jaw dropped. The arrogance melted away like sugar in the rain. His face went from annoyed to confused, and from confused to the purest, most absolute panic.

The color drained from his skin, leaving behind that sickly grayish tone of sheer fear. His wide eyes jumped from me to them and back to me. He opened his mouth to say something, but no sound came out.

His hand, which was still holding a piece of the biscuit, went limp, and the biscuit fell. It hit the china plate with a dry clink, then rolled onto the floor, breaking into crumbs. A tiny sound, the sound of the end of his reign.

The silence in the dining room was so thick, it felt like it had weight. The only sound was the slow, steady ticking of the grandfather clock in the next room, each second marking Jeremiah’s agony. He was frozen in place, his face a gray mask of terror.

His eyes, wide and disbelieving, darted from one face to another like a cornered animal looking for an escape route where there was none. He looked at me, and for the first time I saw in his eyes not anger or contempt, but a terrified question. Mom, what have you done?

I didn’t have to answer. Mrs. Bernice Johnson did it for me with her actions. With a calm that was both terrifying and magnificent, she took a step forward.