Nurse Fired for Saving a Marine — 25 Hell’s Angels and Two Helicopters Escorted Her Home

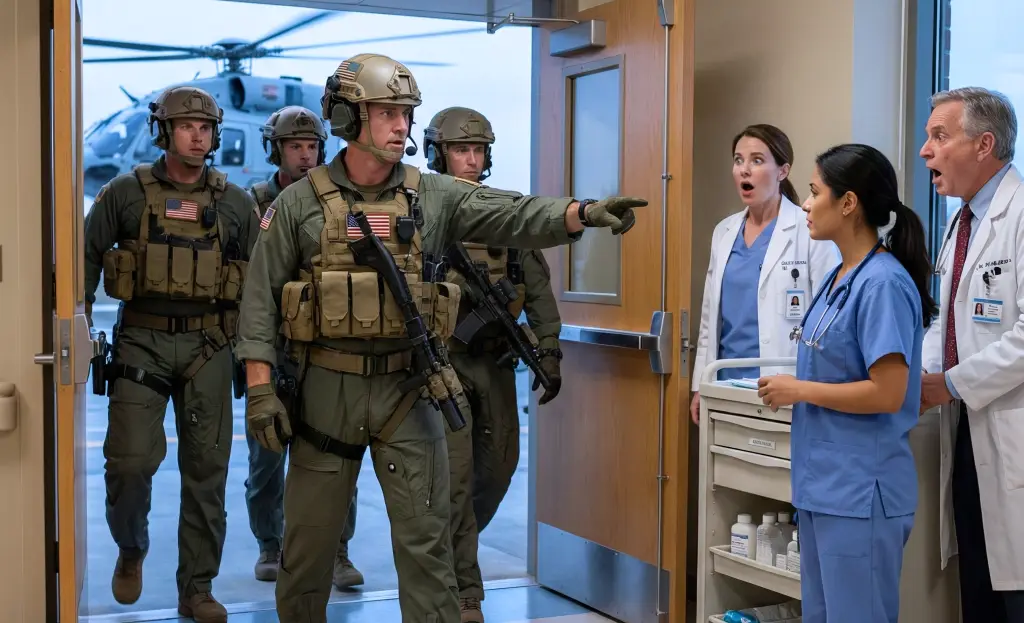

When trauma nurse Sarah Mitchell pushed past Dr. Richard Thornton to inject epinephrine into a dying Marine, she knew it would cost her everything. What she didn’t know was that the Marine’s uncle had already made three phone calls: one to his Hell’s Angels chapter, one to a Marine Corps colonel, and one that went straight to the Governor’s mansion.

Hospital administrator Patricia Weston smiled as security escorted Sarah out. «You’re nobody,» Patricia whispered. «You’ll never work in healthcare again.»

Forty-five minutes later, Patricia would be the one escorted out in handcuffs. Because when you mess with someone under the protection of both the Marines and the Hell’s Angels, you learn a hard lesson. Some people aren’t nobody. They’re untouchable.

Lance Corporal Marcus Webb wasn’t supposed to die in a hospital parking lot in Riverside, California, on a Tuesday afternoon. The 23-year-old Marine had survived two deployments to Afghanistan without a scratch, only to have his throat close up from an antibiotic allergy sixty feet from the emergency room entrance. His lips were turning blue.

His oxygen saturation, the measure of air reaching his brain, had dropped to 68 percent. At 70, you pass out. At 60, brain damage begins. At 50, your heart stops. Sarah Mitchell’s hands moved with the precision of 20 years in trauma nursing.

She had the IV line in his arm before Dr. Richard Thornton had finished pulling up Marcus’s file on his tablet. Her fingers found the epinephrine vial in the crash cart. One milliliter. Standard dose for anaphylaxis.

She drew it up, checked for air bubbles, and looked at Thornton. He was staring at his screen, scrolling through insurance authorization protocols, his face tight with the kind of fear that comes from caring more about liability than life. Sarah didn’t wait.

«I’m not watching another Marine die on my watch,» she thought. She pushed the medication. The effect was immediate.

Marcus gasped, a horrible choking sound that was the most beautiful thing Sarah had heard all day. Color flooded back into his face. His chest rose and fell. The oxygen monitor climbed: 72, 78, 85. He was breathing. He was alive.

Dr. Thornton looked up from his tablet, and his face went cold. Not relieved. Cold. His voice was flat when he spoke.

«You just ended your career, Mitchell.»

Sarah looked down at Marcus. The Marine Corps tattoo on his forearm, an Eagle, Globe, and Anchor, was still visible beneath the IV line. He was someone’s son. Someone’s brother. And now, because of what she’d just done, he’d get to go home to them.

Sarah had no idea that the Marine she’d just saved was about to save her back, in a way that would make national news. But first, she had to lose everything.

County Memorial Hospital in Riverside, California, used to be a place where nurses like Sarah Mitchell could practice medicine with autonomy and respect. That was before the corporate acquisition. It was before the new administration, before Patricia Weston arrived with her MBA, her protocols, and her complete absence of clinical experience.

Sarah Mitchell was 47 years old, a 20-year veteran of emergency nursing, and a widow. Her husband, Marine Staff Sergeant Jake Mitchell, had died three years ago after a brutal fight with cancer—the kind that starts in the lungs and spreads before you can catch it. Sarah kept his dog tags in her scrub pocket.

Some nights, when the shift was slow and the fluorescent lights hummed too loud, she’d touch them and remember what he used to say. «Do the right thing, even when it costs you.» Today, it had cost her.

Patricia Weston was 38, sharp-featured, and had never worked a single clinical shift in her life. She’d been hired to «optimize operational efficiency,» which translated to cutting costs and eliminating liability. Within her first month, she’d implemented a new policy that made Sarah’s blood boil every time she thought about it.

All emergency medications, even in life-threatening situations, required physician authorization before administration. Not physician supervision. Authorization. As in, wait for permission while the patient dies.

Dr. Richard Thornton, the 52-year-old chief of emergency medicine, had backed Patricia’s policy without hesitation. He was the kind of doctor who wore his stethoscope like jewelry and viewed nurses as support staff, not partners. He’d told Sarah once, in front of the entire department, that nurses were there to execute orders, not think.

Sarah had violated the policy twice before, both times saving lives: a diabetic in hypoglycemic shock and a child having a seizure. Each time, Patricia had called her into the office for a warning. Each time, Sarah had stood her ground.

«I took an oath,» she’d said. «First, do no harm. That includes not standing by while someone dies because you’re worried about paperwork.»

The other nurses—Maria, Deshawn, Jessica—would whisper their support in the break room, but none of them would speak up publicly. Patricia had fired six nurses in eight months. The culture at County Memorial was no longer one of healing; it was one of fear.

What Patricia Weston didn’t know, as she sat in her office that afternoon drafting Sarah’s termination letter, was that Marcus Webb had already sent a text message from the ambulance before they’d even reached the hospital. Three words, sent to his uncle: Angel saved me.

And 45 minutes later, when Marcus was stable and coherent enough to send a second message, he added the details Patricia would come to regret. They fired her for it. Name: Sarah Mitchell.

By the time Patricia pressed send on the termination email, that second text message had already reached a motorcycle clubhouse in Riverside. It had reached a Marine Corps Colonel at Camp Pendleton. And it had reached a California State Senator who owed a man named Raymond Webb his life.

The Human Resources office at County Memorial Hospital smelled like fear and cheap coffee. Sarah Mitchell sat in a gray fabric chair that had seen better days. Her hands folded in her lap to hide the trembling.

These were hands that could start an IV in a moving ambulance. Hands that had held the hearts of trauma victims during open-chest resuscitation. Hands that had steadied countless frightened patients. But right now, facing Patricia Weston and Dr. Richard Thornton across a faux wood table, those hands felt useless.

Patricia’s voice was clinical, detached, rehearsed. She’d clearly practiced this speech.

«Gross insubordination. Violation of physician authority. Creating a hostile work environment.» She tapped a manicured fingernail on the manila folder in front of her. She didn’t look at Sarah. She looked at the paper, as if the paper were the person being fired. «The list is extensive, Ms. Mitchell.»

Sarah took a breath. The air tasted like recycled antiseptic and institutional cruelty. «I saved his life, Patricia. Marcus Webb. He’s alive because I didn’t wait for authorization while his oxygen saturation dropped into the danger zone.»

Dr. Thornton shifted in his seat. His white coat was pristine, starched, and probably cost more than Sarah made in a week.

«You undermined my authority in a critical situation,» he said, his voice smooth and oily. «You are a nurse, Sarah. A nurse. You don’t make those determinations. You execute orders. When you pushed past me to access that medication, you created chaos.»

Sarah felt something crack inside her chest. «I created a heartbeat, Richard. His oxygen was at 68. Another 30 seconds, and—»

«That is enough,» Patricia cut her off, finally making eye contact. Her eyes were devoid of empathy, cold as a ledger sheet. «The decision has been made. Dr. Thornton has formally requested your termination, effective immediately. We are revoking your access to the electronic medical record system as we speak. Security is waiting outside to escort you to your locker.»

The silence that followed was suffocating. Sarah looked at Thornton. He offered a small, triumphant smile. It was the smile of a man who had never been told «no» in his life and wasn’t about to start tolerating it from a 47-year-old nurse with a mortgage and a dead husband.

«You’re making a mistake,» Sarah whispered. It wasn’t a threat. It was a diagnosis.

«The only mistake,» Thornton said, standing up and buttoning his pristine coat, «was thinking you were indispensable.»

The walk to her locker felt like a funeral procession. The security guard waiting for her was Eddie Henderson, a 62-year-old man who’d worked at County Memorial for 15 years. Sarah had helped his daughter, Keisha, get a scholarship two years ago. Keisha was in her second year now, thriving.

Eddie’s eyes were apologetic, sad, confused. «I’m sorry, Sarah,» he mumbled as she opened her locker.

«It’s not your fault, Eddie,» she said, trying to keep her voice steady. But it trembled anyway.

She dumped the contents of her locker into a small cardboard box someone had left by the staff room. A stethoscope. A framed photo of Jake in his dress blues—the one taken right before his last deployment. A ceramic mug that said Nurses: saving your ass, not kissing it. A half-empty bottle of Advil.

Twenty years of service reduced to a box that wouldn’t even fill a grocery bag. She clutched it to her chest and walked through the emergency department one last time.

The other nurses—Maria, Deshawn, Jessica—wouldn’t meet her eyes. They knew what was happening. They knew that if they spoke up, if they defended her, Thornton and Patricia would come for them next. Only old Dr. Patel, who was retiring next month and didn’t care anymore, squeezed her shoulder as she passed.

«You did right,» he whispered.

The automatic doors of the emergency entrance slid open with a mechanical hiss. The California afternoon heat hit her face like a slap. Sarah stood there for a moment, the box digging into her forearms, and looked back at the building where she’d spent two decades of her life.

Security cameras mounted above the entrance had caught everything. The moment she’d pushed the epinephrine. The moment Marcus had gasped back to life. The moment Thornton’s face had gone cold with rage.

By the time Sarah took her first step into the parking lot, that footage was already on its way to a Marine Corps colonel in San Diego and to a clubhouse in Riverside with a skull flag hanging outside.

The parking lot stretched before Sarah like a desert. Her car wasn’t here. It was six blocks away at Mike’s Auto Shop, sitting on a lift with a failed transmission. Twelve hundred dollars she didn’t have. Twelve hundred dollars she definitely didn’t have now that she’d just lost her job.

She started walking. The cardboard box felt heavier with each step. The California sun beat down on her blue scrubs, already damp with sweat from the stress of the termination meeting.

The sound of the hospital faded behind her. Ambulance sirens. The beeping of monitors. The organized chaos that had been her entire adult life. Now it was just the hum of traffic on Riverside Avenue and the sound of her own sneakers on hot asphalt.